If it sounds good, it is good

This post is about art. And if you think I’m unqualified to speak about art, well, that’s where you’re right. But I did get a payout from ASCAP one time, so I’m going to spend whatever capital that affords me on this inconsequential blog post. Which is probably still a stretch.

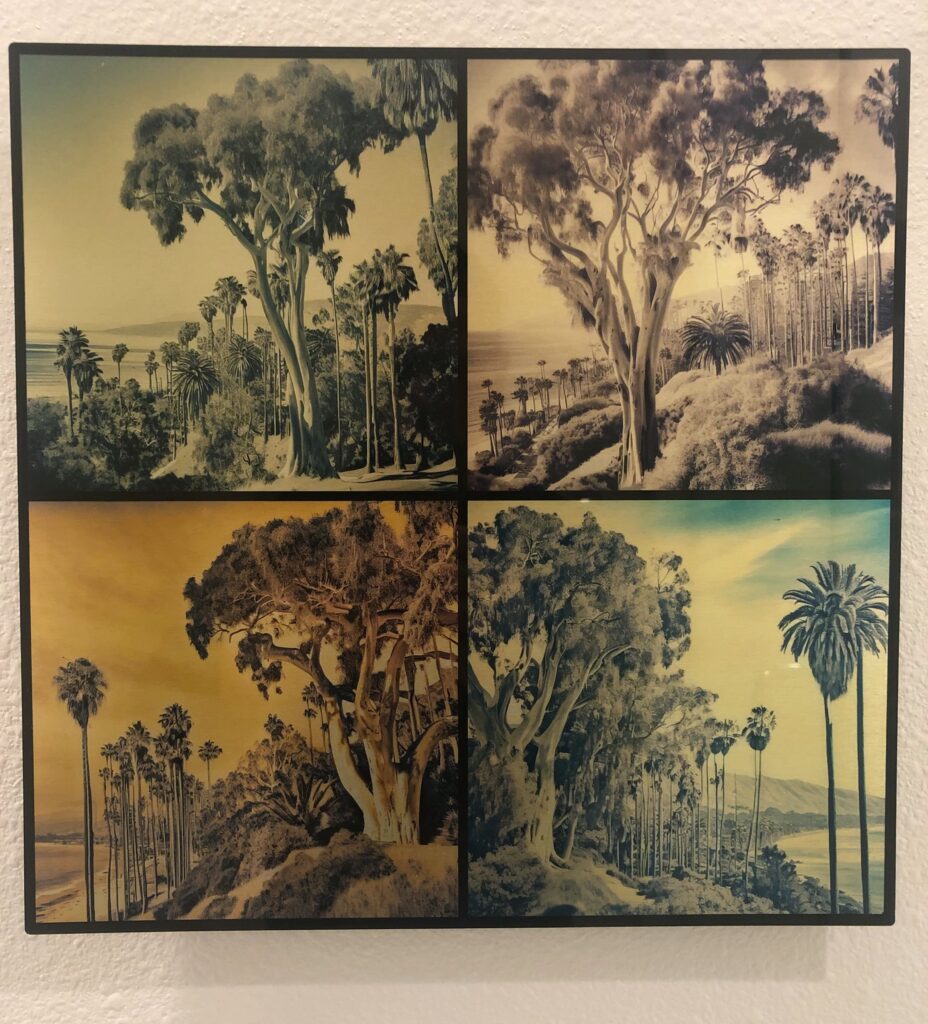

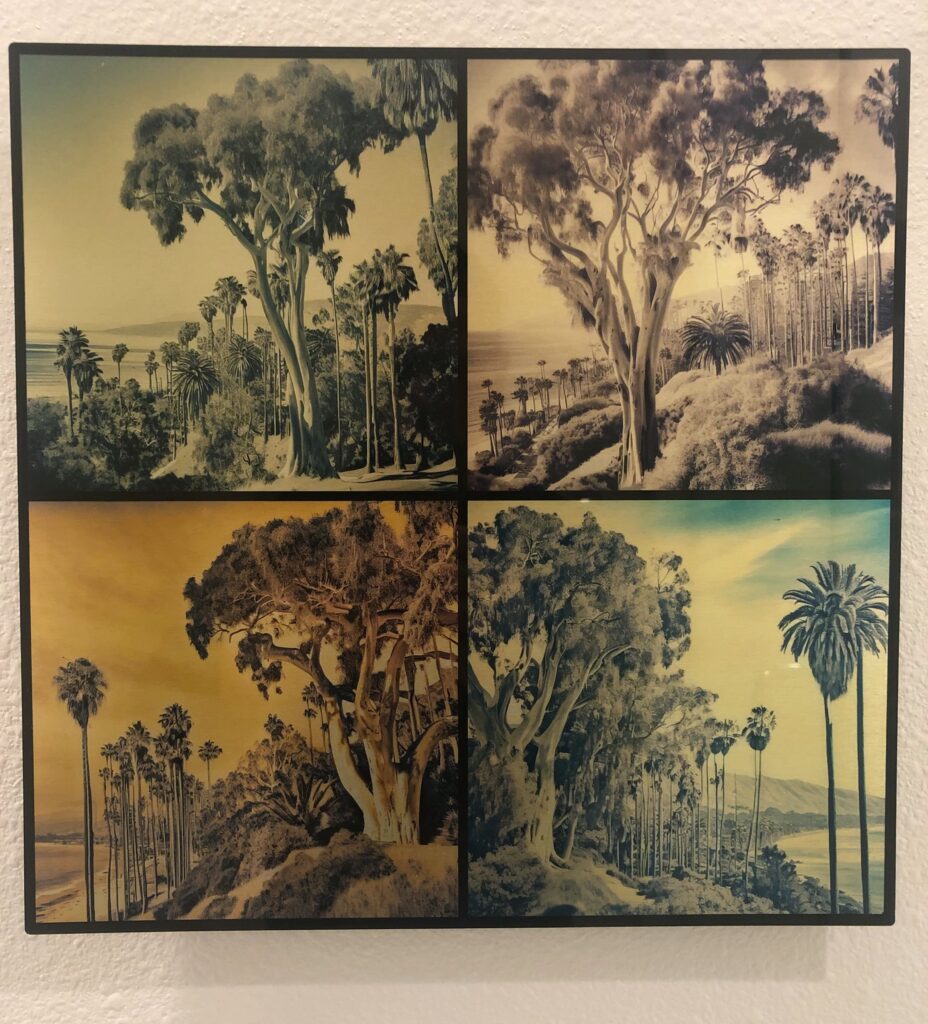

Generative AI has advanced at a rapid pace– just a few years ago getting a computer to produce output like this was impossible. Now, with a simple text prompt, a computer can generate a rich depiction that is satisfying to a human eye, in at least some cases.

It’s not the same as a human artist. I don’t really care one way or the other, but objectively, it isn’t the same. At least not yet. The computer is generating an amalgamation of human-made art (the training set) based on the text prompt. That said, it’s remarkable how effective this is to the viewer, and I think this is an important insight.

The title of this post is a Duke Elligton quote, and it’s one that I think of often. He said, “If it sounds good, then it is good.” It is a dismissal of any high-minded criticism of art. The emotional effect on another human being is what matters, and if a piece of music or other art has that, then any criticism withers into irrelevance. The virtuosity of the artist doesn’t matter. The originality of the composition doesn’t matter.

Generative AI, with its massive training set, is the ultimate rip-off artist. Part of me finds that annoying on visceral level– the part of me that sympathizes with the suffering of artists: the struggle to create originality and find impact in novel ways. Still, it is also true that artists learn by copying great paintings, or playing cover versions of great songs. These are respectable ways to build artistic skills, and similar to what Generative AI does today. “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.” – T. S. Eliot. It’s not just a learning mechanism, it’s part of the highest echelons of art. Take it from this ASCAP-paid artist: it happens all the time in music. Or be wise and ignore me, and instead take it from this New Yorker article.

Thus, the fact that industrial-scale, automated amalgamation can result in art that has an impact on humans can be consistent with the idea that: that’s what artists do. Not exclusively, but at least in large fraction.

The picture at the top of this post has four views in it– none of them are real places. They share similarities with the coastline of Santa Barbara, including the types of trees that I put in the text prompt, but the place doesn’t exist, and it certainly wasn’t photographed by Ansel Adams (though he did take some photos of Santa Barbara). Yet it still evokes a similar feeling, to me at least. If it sounds good, then it is good.

I made some more items with Dall-E, including drawings of my dog and cat in the format of a Studio Ghibli film, and I like the results:

I also had it make a photo of Winston (our 150 lbs black Newfy dog) and Humphrey (our grey British Shorthair cat) on the pond in Inokashira Park on a swan boat. The resulting image only has Humphrey on the swan boat, but the depiction is fantastic. Much better than I would have expected from a human artist.

In closing, two remarks: First, automated amalgamation alone can provide output that has much of the effect of art. I still hold that art involves more than amalgamation. I think. Second, remember that these computing architectures are built using deep learning, which are usually randomly initialized and emerged from ideas inspired by neural circuitry. It wasn’t some top-down, hand-designed algorithm that ended up working. Pure learning, with all of its potential limitations, works quite well in this application.