ELIZA.EXE

When I was a kid, maybe about 12 years old, I was in my bedroom (in the basement), at my computer that I bought with my paper route money (it was $1400 and made by Packard Bell). I was going through some floppy disks my dad no longer needed and had given to me to use as I wished– probably deleting and writing my own files to them. I was checking out the contents to see if there were interesting things on them. Much of it was data from his work, but some items were interesting.

I came across a floppy disk that contained a file entitled “eliza.exe”. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was a famous program. It was written in the 1960s. It was already decades old by the time I got to try it, and it’s about 60 years old as I write this blog post.

That little program is still relevant today. In fact, it is nearly the whole game of social media and politics today. This humble little file: eliza.exe

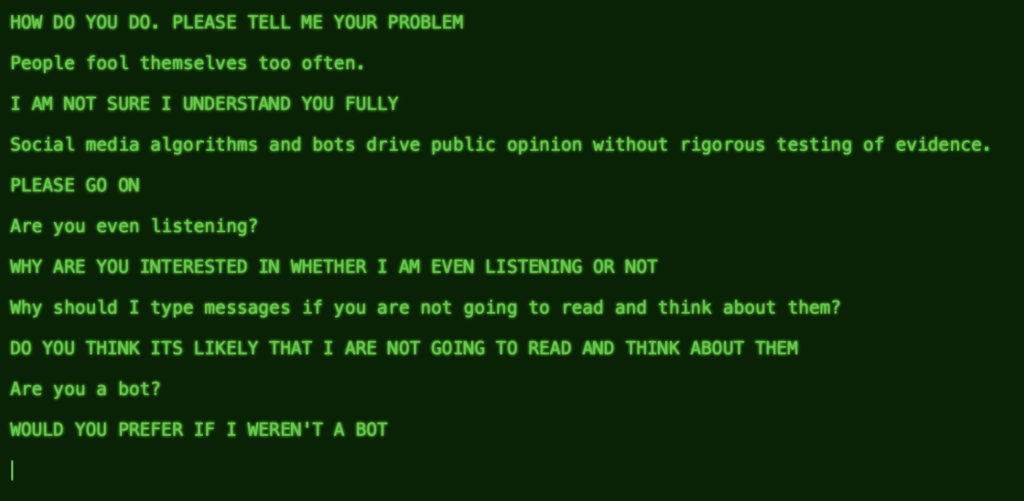

The program worked on the command line. No windows. No fancy display. Just text.

It was a simple, formulaic chatbot, that often revealed its limitations. What was interesting was how much of an apparent conversation you could have before those limitations were overwhelming and ruined the illusion of having a discussion with a person.

Here’s a key quote, from the author of Eliza, Joseph Weizenbaum. He wrote:

“What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful, delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

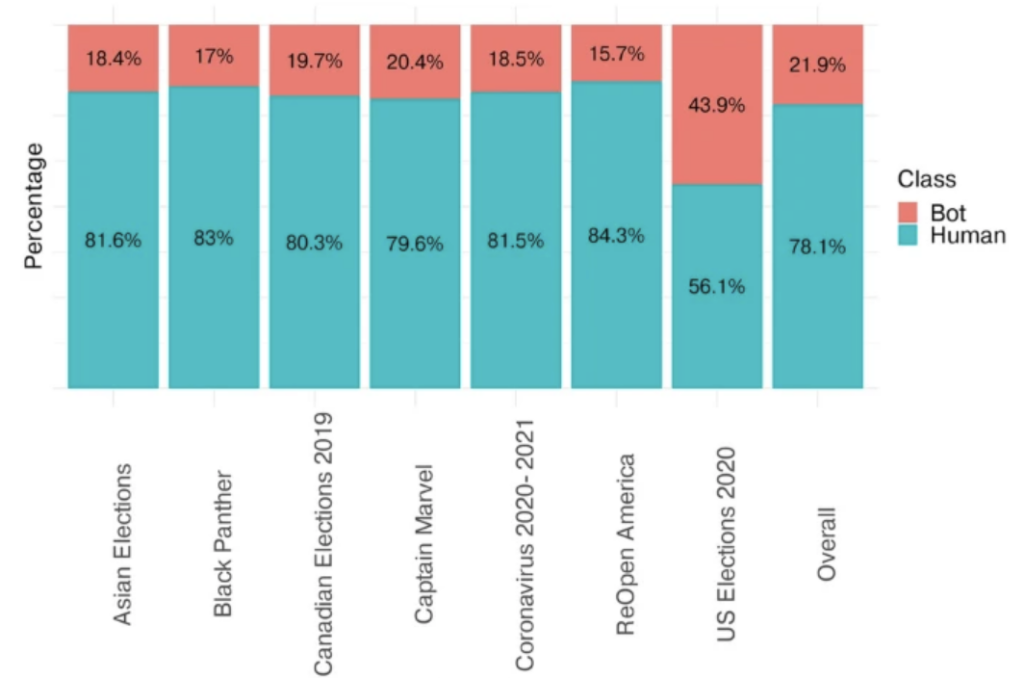

Today’s chatbots are more sophisticated, and with modern large language models (LLMs, like ChatGPT), they can keep up appearances for quite some time. These modern chatbots, coupled with algorithm-driven social media, lead many people to spend hours online consuming content, only some of which is authentically from other human beings. When bots and algorithms drive what users read, then the programmers have tremendous influence over public perceptions and actions. This is already a part of politics. That ship has sailed, maybe as much as a decade ago.

So Eliza was the pioneering experiment. Even this simple program from the 1960s demonstrated a truth about human behavior: we fool ourselves. We do it because it is easy and satisfying. And when we do it on a massive scale like we do today, involving a significant fraction of the population, it moves politics, elections, and power. Those flows of politics are under control of those who control the algorithms and the bots, and those can be relatively few people. And they probably act like most people do, with their own interests in mind.