Patents and academic research

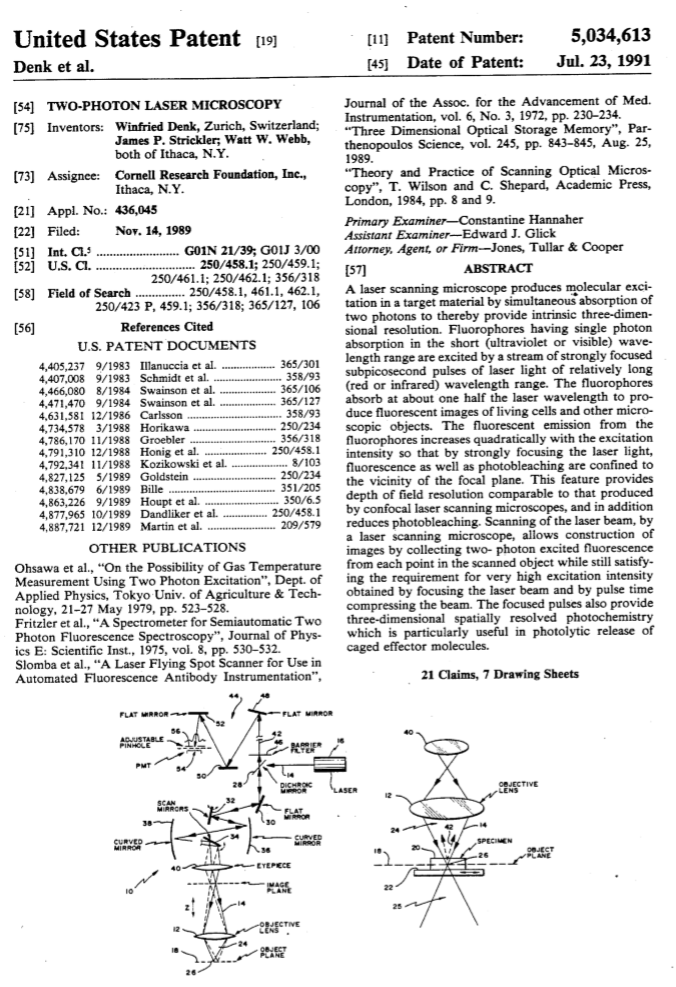

This is about the research exemption for patents. Early in my training, I was taught that academic researchers didn’t need to worry about patents, because they could build whatever they wanted for research purposes without licensing anything. This often came up in discussions before the two-photon microscopy patent expired. People building their own two-photon microscopes for research work could do so without worrying about patents.

Actually, we can’t.

There was a 2002 case involving John Madey and Duke University (Madey v. Duke) and the court concluded that using patented technology as a part of a broader research program is NOT exempted by the research exemption. In that case, the court thought that building a patented device to see if (and how) it works is okay. However, you can’t then go on using the device for further research without first getting permission. The idea is that once we’re using it for another experiment, then we’re doing “business”. This idea was not popular in academia when it came out (PDF link), but as far as we know, it has not been resolved differently since then.

According to the Federal Circuit, the experimental use defense is “very narrow and strictly limited.” [65] Reiterating its holdings in [the] Roche and Embrex [cases], the Federal Circuit stated that the experimental use defense is limited to uses “for amusement, to satisfy idle curiosity, or for strictly philosophical inquiry,” and that the defense is disqualified as long as a use has any “definite, cognizable, and not insubstantial commercial purposes.” [66] Relying on [the] Pitcairn [case], the Federal Circuit also disqualified any conduct from the experimental use defense if the conduct was in keeping with an infringer’s legitimate business, “regardless of commercial implications.” [67] The court stated that the legitimate business of a research university includes any project designed to “educat[e] and enlighten[] students and faculty,” to “increase the status of the institution,” or to “lure lucrative research grants, students and faculty.”[68]

Michelle Cai (source, PDF)

So we can build a patented device to see how it works, but we can’t then go and use it as a component of a system that we use for other research. That’s not exempted from patent protection.

Practically, it’s unlikely for anyone to bring a case against a single PI working in an academic lab. But that alone is not a great solution to this situation.

We’ve been thinking a lot about this for three reasons. One, we’re scientists, and part of our job is to build on what other people have done to advance research. If we have to license everything we replicate and use that is covered by patents, that’s a significant administrative burden and potentially throttles scientific progress. Two, we run this web site, and part of the point of it is to share technical information to advance research. Some of what we recommend technically requires licensing from patent holders. Three, we’re currently running an NSF grant where we’re supposed to disseminate tech to other labs for research, but some of it is covered by patents (including work from my own lab). It seems improper to encourage activities that infringe on patents, even if enforcement is unlikely. However, ceasing these activities impedes scientific progress, which is what the taxpayers pay us to advance. Thus, there is a conflict that should be resolved.

Some potential solutions:

#1. Federal legislation. Good luck with that.

#2. New case law. Slow, and still might not solve the problem.

#3. A patent truce among stakeholders. Universities and other institutions could simply agree to not sue individual PIs over patent infringement in cases where the work is purely for academic research. This also seems unlikely to happen, but there is precedence. Silicon Valley firms have used a patent truce before.

In the mean time, we should obtain formal permission from individual patent holders as it comes up. Universities are already equipped to deal with MTAs and other exchange agreements. It’s cumbersome and slows research, but this is the system we have at the moment.

Patent truce sounds good, as academia doesn’t need one more admin concern for PIs. But research institutions are more and more blurring the line with business (see the rise of public-private consortiums, industry-funded PhD positions and patenting by research labs), and also act as start-up incubators. So I don’t expect this issue to go away.

The research exemption is an interesting point. The US law sets extremely tight limits on the exemption (ultimately, if a person has any actual interest in the patented technology, the exemption doesn’t apply). EU patent law is a bit more lenient (here the exemption covers implementing a patented technology for test and verification purposes), but still doesn’t allow actual use of the patented technology. Even in research. An interesting read on this is “Research Exemption/Experimental Use in the European Union: Patents Do Not Block the Progress of Science”, Hans-Rainer Jaenichen and Johann Pitz, 2015 (http://perspectivesinmedicine.cshlp.org/content/5/2/a020941.full.pdf)

The paper Christian mentioned is well worth reading. It looks like the UK version of the Experimental Use Exemption is actually the best (for science). With most of them, even in the EU, it appears that you can do research *on* the subject of the patent, but not *using* it. Good for optics development work perhaps, but not so much for neuroscience*. The UK version seems a bit more lenient, but I’m not sure I completely understand the details.

* I am here taking the perspective that it is good to allow us to build scopes for research purposes using previously patented principles, which some of course might disagree with.