Write it down. Analyze it now.

This piece from Eve Marder resonantes with me. Just a couple of notes to elaborate on it.

Write it down. I tell people in my lab this all the time. Work done that is not recorded fades quickly in value. There is particularly a tendency to avoid writing things down or recording data when setting up new experiments. Experimenters take a look and simply note an impression. This is a common but colossal blunder. You can’t troubleshoot properly if you’re not taking notes. Impressions shift over time. Memory is imprecise and unreliable. See nothing in 2p? Record the specs and take some images. That way we can do an apples-to-apples comparison later. Maybe it was low expression, or maybe the laser power was just too low. You can’t know if you don’t carefully record what you did. If you’re not writing it down, then you’re just screwing around.

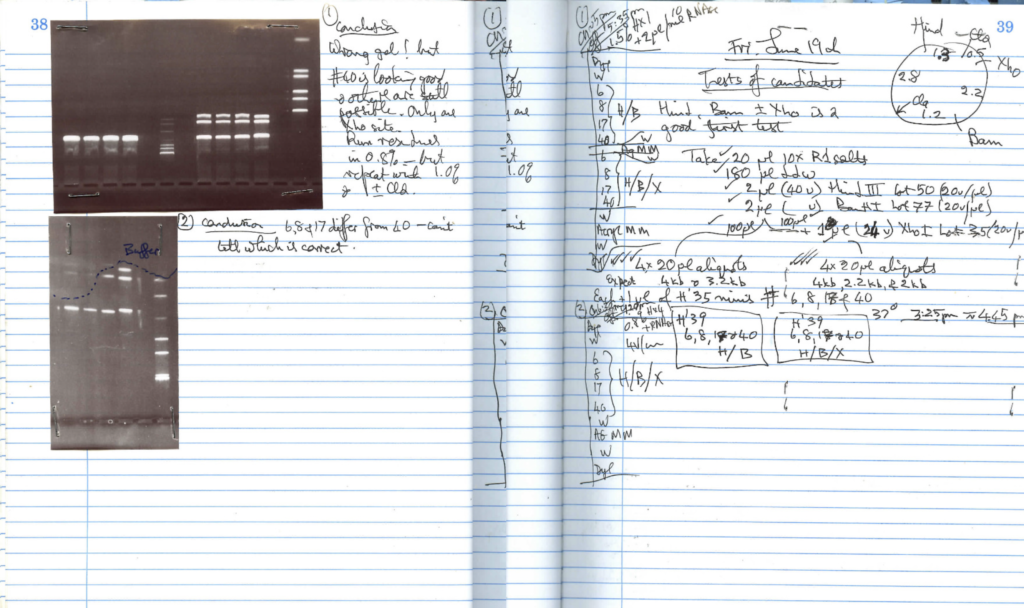

I only chatted with Oliver Smithies a bit when we were both at UNC-Chapel Hill, but it was enough for him to leave a strong impression on me. He had a tradition of doing what he called “weekend experiments”, where he let his rigor slip a little for the sake of a pleasurable day in the lab exploring biology. For example, he might be less precise measuring out reagents. Or try something a bit illogical. However, he always wrote everything down. He kept detailed lab notebooks, with quantitative information about what had been done, illustrations of what he saw, and contemporaneous notes on what his impressions and thoughts were. Often slides in his talks would simply be photographs of pages from his notebook. UNC has archived his lab notebooks. How many of us are keeping lab notebooks that are worth archiving?

Another point Eve Marder makes is that the very act of writing helps reveal truth. We formalize findings and learn what insights we can draw from our results. Anyone who has written a fellowship or grant proposal can attest to the value in refining our scientific thinking. It’s not always valuable enough to justify writing grants that don’t get funded, but it is certainly valuable. Even writing emails to colleagues (and sometimes even social media posts) can help us refine our scientific thinking and experimental strategies, and better articulate results and insights.

Analyze it now. People often take massive amounts of data and then sit on it without analysis. For months sometimes. In the meantime, they may take many more massive amounts of data. Still not analyzing the data until later. That is often foolish. Maybe there are cases where it can be by design, but it is often not. What if you’re doing the experiment wrong and it won’t stand up to the analysis you want to apply? Maybe you need to vary some parameters of the experiment. You won’t know until you analyze it. You could be wasting massive amounts of time taking data that cannot reveal the insights you’re looking for. I recall commiserating with David Tank about this years ago. It’s somewhat an organic consequence of the growth of datasets in systems neuroscience, and the complexity of their analysis. However, that’s not an excuse. I try to get my people to analyze their data as soon after taking it as possible. Ideally within hours.

It reminds me of a story Allan J. Tobin told me back at UCLA. When he was a young student, and was just learning in the lab, he was eager to immediately analyze some results from an assay. The graduate student teaching Tobin told him that he usually waited a week or so and then did a batch of analysis. Tobin couldn’t stand to wait– he was so excited to find out what the result was. He later looked for this characteristic when recruiting for his own lab. Students with this kind of eagerness for results can go far, and we should cultivate such eagerness and prompt analysis when we can.

[…] Write it down.If you didn’t record it, it doesn’t count.It turns out that we can’t say this enough to students. […]