The NSA, Eisenhower, and Research

A famous speech from 1961 is being quoted in the media recently, and it might be interesting to Labrigger readers that the same speech offered some thoughts about the future relationship between science and the federal government.

Revelations from Edward Snowden and others have revealed a broader scope of surveillance than most Americans were aware of. As a result, now, all three branches of the US government are working on how domestic surveillance, and its oversight, should be carried out.

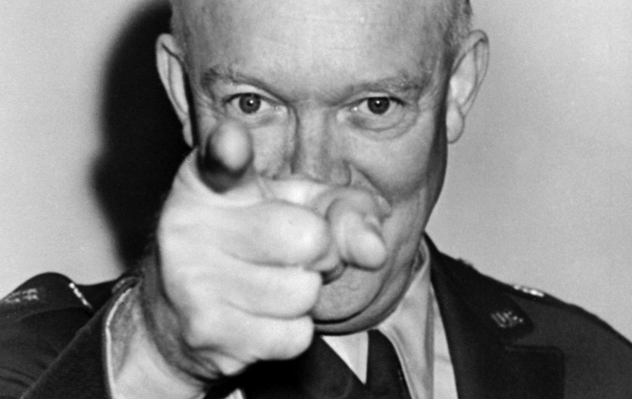

Let’s retrace our steps to how we got here. A good place to start, or at least a good waypoint, is Dwight D. Eisenhower’s speech in 1961. This was a sort of one-sided exit interview at the end of his presidency, where he gave his perspective on the future for America. Although the speech was optimistic in parts, it was fairly heavy on caution. In particular, this speech is often cited for his warning about the growing influence of the “military-industrial complex”, which is relevant for today’s discussions regarding the NSA.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense. We have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions.

Now this conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every Statehouse, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet, we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources, and livelihood are all involved. So is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

(emphasis mine)

This warning carries great weight because of who said it. Eisenhower was the most credentialed military man to become US president, at least since the 20th century if not of all time. He was a 5-star general (there are only about 10 such highly ranked military personnel of all time in the US). He served in WW1, was a major leader in WW2, and was the first supreme commander of NATO.

He was not a researcher.

However, in the same speech, he had this to say about research.

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades. In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers. The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present — and is gravely to be regarded.

Eisenhower is describing how research had evolved from an independent affair, nurtured in universities– to a stage where the federal government subsidized and supported it*.

The continued evolution has brought us to the current state, where the federal government almost completely funds research, to the extent that it is difficult (or at least rare) to run an entire research program outside of the support structure of federal grants.

* I think this quote from David Hubel (who was doing his best work right around the time of Eisenhower’s speech) captures this intermediate stage: “NIH support was generous and we never had to spend more than a few days every half-decade writing grant proposals.” (source)